When you hear thunder:

For 33 years I have had a job that finds me working or training in periglacial environments where lightning is the main hazard in summer, and avalanches in winter. Just head up a popular trail in the Rockies such as the Iceline Trail in Yoho, or Healy Pass in Banff. If you happen to hear thunder while you are there, you can easily find people still casually sliding along the trail, picnicking on top of a nice flat exposed rock, assembling in a large guided group for photo sessions at the top of the Pass, etc. They are on holidays, and where applicable: it seems that the guide in that photo shoot scenario was chosen primarily due to a demonstrated fluency in another language, they are blissfully unconcerned about that clap of thunder. The eco-tourism environment is different from situations where substantial buildings or fully enclosed metal vehicles are the recommended shelters, but I get the impression - from the first question I am often asked, that perhaps many are so busy worrying about the chances of a human-wildlife conflict (primarily bear it seems), they have forgotten there might just be some higher priority objective risk assessments they should be making. If they had, they would showing the same concern for finding suitable temporary shelter as they did when they got that first mortgage. To paraphrase what my co-worker Brad once said, "you can always tell someone who's been hit by lightning, you just can't tell them much!". (My spouse Sharon, upon hearing that, remarked, "you've apparently been hit on numerous occasions then").

Look Mom, I'm a lightning rod! (Iceline Trail, Yoho National Park)

Lightning safety is a risk management procedure. Lightning hazards can be mitigated by advanced planning. The distances from lightning Strike A to Strike B to Strike C easily can exceed more than 10km. Hear thunder? How much time is needed to get to shelter? Two to four minutes is suggested. Suspension of activities is very site-specific, and can be a problem if you are above treeline. As you are hiking along, make mental notes as to where you passed a feasible shelter point that you can retreat back to if need be. For general situations, you start to make a plan when thunder is first heard. Immediately start to assess where you best shelter point can be accessed without having to make the mistake of trying to outrun the lightning! Once you have attained a shelter point, the experts also recommend waiting to resume activities 30 minutes after the last observed lightning or thunder, even though this protocol may seem excessively conservative in many situations ("we'll never get anywhere under such strict guidelines"). It is a case-by-case risk management decision. And yes, safety and productivity sometimes are incompatible.

Lightning causes the simultaneous emission of a broad band of radio frequencies. The signals can be heard from a few hertz to hundreds of megahertz. Most of lightning's effective radio energy is concentrated in the 1 to 30 kilohertz region. This region of the radio spectrum is considered the VLF, or Very Low Frequency, radio range. This is where the Anytone 3318'D' model is worth considering. While it cannot get as low as 30kHz, it is capable of receiving on the LW band from 520-1710 kHz. This is still a useful RF window for hearing atmospheric disturbances such as lightning that present themselves as static bursts that can be heard if you're monitoring the LW Band in the radio.

This is most useful if you suspect lightning activity, and you are about to commit to an extended period of exposure such as crossing a pass above treeline (for those of you that have traveled the Brazeau Loop, consider the Jonas Pass section where you face 10km above the trees as a good example of a large problem with regard to risk exposure), traveling on a glacier, or a route on a ridge or face. If you can listen for approaching lightning and determine it may be headed your way, you may be able to determine if you have a window of opportunity to complete your objectives while on that landscape feature where you will be exposed, or if you should seek the best shelter you can find, settle in, and wait for the active lightning cells to pass before you proceed:

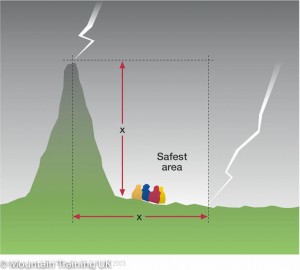

One option I think is often overlooked in mountainous terrain is the "Shadow":

From Langmuir (Mountaincraft and Leadership, 3rd Edition):

You can get a shadow from a 7m or taller cliff where the safe zone is between 3m from the base out to the height of the cliff - this means standing 5m from a 7m cliff should reduce your chance of a lightning strike (note - reduce - there is still a chance you can get hit, there is no 0%). There is a diagram on page 227 of 3rd Edition - I can't find one to link to, unfortunately. He doesn't say how steep the cliff should be, though.

If you enter a cave for shelter (or dive under a boulder) - you must have at least 3m head room (so - 5m total) and 1m to either side.

There are numerous good guides to safety practices. Here is one that I often defer to because it addresses an area where I commonly find myself, in rocky terrain:

If you’re out climbing on the rocks or in the mountains and a thunderstorm sweeps in, you're in a dangerous situation to be struck by lightning since you're probably in an open exposed place like a ridge, cliff-top, or mountain summit.

Follow these 10 tips for climbers to minimize your risk and stay safe from lightning when you're caught in a dangerous storm.

Quickly descend to a lower elevation: Descend and find a less exposed place.

It’s best if you’re away from the direction of the approaching thunderstorm that is accompanied by lightning.

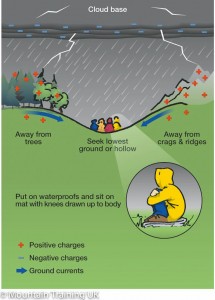

Don’t be the tallest object around: To avoid lightning, don’t stand in open areas like meadows or mountain tops. Instead take shelter in a thick forest and avoid taking cover beneath isolated trees or a tree that is taller than nearby trees. If there are no trees around, hunker down in a depression and squat. Don’t lay down on the ground.

Keep away from objects that conduct electricity: These include water, metal objects like climbing equipment, metal fences, and power lines. Take off any climbing pack with an internal or external metal frame and hang allmetal climbing gear well away from you.

Wet ropes can carry current: A wet climbing rope also makes a perfect electrical conductor for lightning to strike you. In a bad storm, consider untying any wet rope from you. If lightning strikes above, the current can pass down the rope and zap you.

Squat or kneel down: It’s best if you use a sleeping pad, empty climbing pack, climbing rope, or anything else that will insulate you from the ground.

Put your feet close together so you will have less contact with the ground and reduce danger from ground currents. Do not lie flat on the ground because strike currents can easily travel through your vital organs.

Spread your group out Spread your group out (a minimum of 15 feet) so that if there is a lightning strike there will be team members available to give first aid assistance.

Don’t hide in small caves or under overhangs: Sitting under an overhang or in a small cave is asking for trouble since lightning will jump the gap from top to bottom by passing through you. I had a friend killed by lightning onPikes Peak when he sat under a boulder overhang above timberline to wait out a storm.

Move to either side of cracks: If you’re climbing and a lightning storm arrives, move away from vertical crack systemswhenever possible. Lightning currents travel down cracks.

Avoid rappelling in lightning storms: Rappelling in lightning storms should be avoided if at all possible. Currents from a cliff-top strike can travel down your wet rope, zapping you. Sometimes, however, rappelling might be the fastest way to reach safety so you might need to take a calculated risk by rappelling…and keeping your fingers crossed!

Don’t lie down on ledges: If you’re on a cliff in a lightning storm, don’t lie down on a ledge or sit with your back against the vertical wall since current can pass through you. Instead try to sit or crouch, preferably on insulation like a rope, on the outside edge of the ledge. Also tie in crosswise so you don’t fall off if struck and keep the rope from under your armpits.

Some other good mountain-specific reads:

- Learn the truth—and myths—about lightning to stay safe on your next adventure

- Roger J. Wendell

- 'Hillwalking', published by Mountain Leader Training UK,